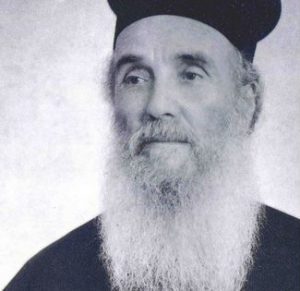

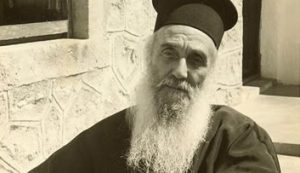

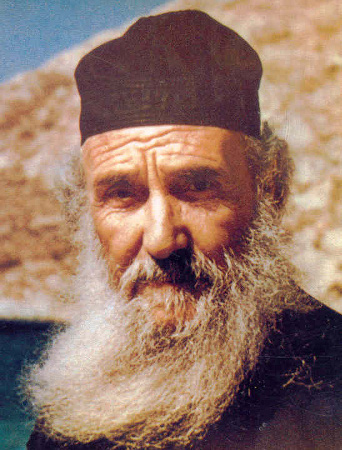

The blessed Elder Amphilochios (Makris) was born December 13, 1889, on the holy island of Patmos, where St. John the Evangelist received and wrote the final book of the New Testament, Revelation. His pious parents Emmanuel and Irene gave him the name Athanasios in baptism. As with many holy elders and Saints of the church, Athanasios was born into a large family of simple country folk. Family stories tell of the piety of Athanasios’s paternal grandparents and the ways in which they were visited by divine grace. Little Athanasios seemed to have an innate sense of the Church’s phronyma and thus refused his mother’s milk on Wednesdays and Fridays. At the tender age of five he managed to convince his godmother, who had just gotten engaged, to call off the engagement and live out the rest of her days in virginity. Athanasios preserved himself from the temptations of the world and, by the age of seventeen, decided with certainty to enter a monastery. His parents were happy to give their blessing, and so the young Athanasios became a novice at the Monastery of St. John the Theologian, Patmos in March of 1906. He quickly became beloved of the aging brotherhood, and progressing in virtue and asceticism, he was made a rasaphore monk in August of the same year, at which time he was given the name Amphilochios.

The blessed Elder Amphilochios (Makris) was born December 13, 1889, on the holy island of Patmos, where St. John the Evangelist received and wrote the final book of the New Testament, Revelation. His pious parents Emmanuel and Irene gave him the name Athanasios in baptism. As with many holy elders and Saints of the church, Athanasios was born into a large family of simple country folk. Family stories tell of the piety of Athanasios’s paternal grandparents and the ways in which they were visited by divine grace. Little Athanasios seemed to have an innate sense of the Church’s phronyma and thus refused his mother’s milk on Wednesdays and Fridays. At the tender age of five he managed to convince his godmother, who had just gotten engaged, to call off the engagement and live out the rest of her days in virginity. Athanasios preserved himself from the temptations of the world and, by the age of seventeen, decided with certainty to enter a monastery. His parents were happy to give their blessing, and so the young Athanasios became a novice at the Monastery of St. John the Theologian, Patmos in March of 1906. He quickly became beloved of the aging brotherhood, and progressing in virtue and asceticism, he was made a rasaphore monk in August of the same year, at which time he was given the name Amphilochios.

The young monk Amphilochios was strict with himself. Aware of his various shortcomings, he devised ways of combating his sinful tendencies, so as to advance spiritually. He was especially strict in his eating and would eat no more than ten mouthfuls of food at each meal, while on fast days he would eat only seven or eight olives. After seven years in the monastery, he had progressed sufficiently so as to be deemed ready to take the Great Schema in March of 1913. Amphilochios’s spiritual father, Elder Antoniadis, performed the tonsure. It is not insignificant that Fr. Antoniadis was a spiritual son of the fathers of the Kollyvades Movement, which had brought spiritual rejuvenation to the Greeks, so afflicted under the Turkish yoke. This helps explain the missionary and ascetic zeal of Elder Amphilochios.

Fr. Amphilochios was completely dedicated to his monastic profession. He did, however, retain the hope of eventually making pilgrimages for spiritual edification. This was realised in 1911 when the abbot of the monastery decided to send the young Amphilochios to Mt. Athos, so as to learn woodcarving. It was a soul-profiting visit that he remembered fondly until the end of his days.

A few years later, in May of 1913, the abbot, recognising Amphilochios’s virtue and progress, secured the agreement of the brethren of the monastery to have him ordained to the diaconate. They sent him to the island of Kos to be ordained by the bishop there. Amphilochios’s concern, however, for his inadequacy and unworthiness led him to change his course. To his travelling companion, one of the brethren of the monastery who was also to be ordained, he explained, “My brother, I am unworthy of such an honour. I would rather go from place to place begging alms, with a clean conscience, than unworthily take on the honour of ordination. Go on in peace, I’m going to head towards the Holy Lands.”

In this way, Fr. Amphilochios’s sense of unworthiness, coupled with his characteristic freedom of spirit and his fervent desire to see the Holy Places led him to travel to Egypt and then on the Holy Lands. He was very moved by his pilgrimage and decided to ask the Patriarch of Jerusalem to receive him as one of the caretakers of the Holy Sepulchre. Although the Patriarch was willing to receive him, the brethren of the Monastery of St. John the Theologian on Patmos insisted that he return to the monastery of his repentance. On his return to Patmos, the brethren “punished” him for his disobedience by sending him to the hermitage of Apollo, to live beside the Elder Makarios. As it turned out, he was very happy there, able as he was to give himself over completely to prayer in the silence of the desert.

From early on, Elder Amphilochios had dreamed of eventually helping his countrymen, spiritually weakened after hundreds of years of Turkish oppression and foreign rule, to discover their spiritual roots and to delve deeper into the spiritual life. Already, as just a simple monk in the monastery, he managed to procure a plot of land on a rocky slope of western Patmos. He built two cells adjacent to the chapel already there and dreamed of eventually building a monastery for women. Eventually, in 1920, God brought Amphilochios his first co-worker in the mission field, Kalliope Gounaris (the future nun Evstokia).

From early on, Elder Amphilochios had dreamed of eventually helping his countrymen, spiritually weakened after hundreds of years of Turkish oppression and foreign rule, to discover their spiritual roots and to delve deeper into the spiritual life. Already, as just a simple monk in the monastery, he managed to procure a plot of land on a rocky slope of western Patmos. He built two cells adjacent to the chapel already there and dreamed of eventually building a monastery for women. Eventually, in 1920, God brought Amphilochios his first co-worker in the mission field, Kalliope Gounaris (the future nun Evstokia).

Significant in the Elder’s missionary endeavours was his ordination to the diaconate in 1919 and to the priesthood soon afterwards, due to the continued pressure of the brethren of the monastery. Though bringing him added responsibilities, his ordination also enabled him to serve the liturgy freely, to receive spiritual children, and to bring the grace of the Mysteries to his mission work. Soon after his ordination he was sent to serve at the monastery’s dependency on the island of Kos. This was also the first period of his missionary travels during which time, in addition to his service as priest in the Monastery of St. John the Theologian, he served as a confessor throughout the islands of the Dodecanese. Much of his time and energy to at the cave of the Apocalypse on Patmos. During this period, he spent a good deal of time with students of the Ecclesiastical Academy of Patmos. His concern was that they mature spiritually and intellectually so as to be useful servants of the Church and society. The many seeds he planted bore much fruit, including numerous elders and abbots or monasteries.

By 1935 a difficult situation had developed among the islands occupied by the Italians. The Italians had managed to influence the Church and the monasteries there by forcing a system of governance upon the Church that made it easy for them to manipulate the Church to their advantage. When the question of the new abbacy of the monastery was raised in 1935, the Oecumenical Patriarch (under whom the Dodecanese are governed ecclesiastically) insisted that this anomalous situation be rectified. The brotherhood elected Elder Amphilochios to be abbot, undermining the authority of the Italians, who wanted one of their puppets elected.

Soon after his election as abbot, the door opened for what would be the seeds of the future women’s Monastery of the Annunciation, fifteen minutes by foot from the Monastery of St. John. Initially the building there was to house a training workshop for knitting and weaving. The secret reason for the establishment of the workshop was to provide an underground school where the children of Patmos could learn Greek letters, as the Italians were on the verge of prohibiting the teaching of Greek to the children. Kalliope Gounaris had by this time moved to Patmos and was to run the school along with the help of some other pious young women.

The Italians got increasingly upset by the Elder’s work and eventually removed him in 1937, exiling him to “free” Greece along with Kalliope Gounaris. In place of the Elder the Italians had one of their co-workers, a monk of the monastery, elected and enthroned as abbot. The small community of the Annunciation that the Elder had managed to organise was now left without their spiritual father during the time of his exile. The Elder, who throughout his life was especially devoted to his nuns, was greatly concerned for them during this period of exile and persecution.

When the elder arrived in Athens, he was given hospitality by the “Zoe” brotherhood in Athens. From there he travelled throughout Greece, eventually reaching Crete, where he was asked to take over the general spiritual fatherhood of the island. His exile ended in 1939, when he was received with great joy back on Patmos.

Occupation of the islands by the Italians was followed by German occupation in 1942. The Elder, exhausted from his exile, decided to not return to the abbacy of the monastery, but spent time at various dependencies of the monastery, and focused his energies on the spiritual and material establishment of the women’s Monastery of the Annunciation. He carefully regulated the monastery’s communal life, providing it with the foundation on which it would flourish. In addition to the monasteries on Patmos and Kalymnos, the Elder had hoped to establish women’s monasteries in other parts of Greece. In time, his prayers and struggles were rewarded as provision was made for monasteries on the islands of Aegina and Ikaria as well as for an ecclesiastical centre and church on the island of Crete.

Elder Amphilochios had a balanced understanding of people and their needs, realizing that man is made up of both soul and body. While he placed the good of man’s soul at the centre of every action, he did not divide this from the other aspects of man. Thus, we see that in addition to his attempts to provide centres of monastic struggle for those who sought such a life, he also sought to provide opportunities for study and for the development of each person’s talents. In 1947, he was given the opportunity to help the orphans of Rhodes, whose material situation was miserable. He organised a small group of his nuns, led by Abbess Evstokia, to establish an orphanage and a unit for pregnant women.

Perhaps more than anything else Elder Amphilochios is remembered for his great love and sacrifice for the suffering people of God. Despite his sickness and weakness, he would receive the faithful with joy. In responding to the objections of one of the sisters, who was concerned for his health, he responded, “I am a servant of the Church and cannot rest”!

The power of his love and prayer for people is attested to in the following incident. Late one afternoon, while the Elder was in Athens, two spiritual daughters visited him. They left the house where he was staying after nightfall and he bade them good night with his blessing, He was anxious, however, for their safety, and as they left he began to pray earnestly for their safe trip home. He was especially concerned as one of the ladies had a problem with her knees and often fell. As they returned home, the infirm lady felt as though she was being lifted up in the air, and her companion verified that she was walking nearly a foot and a half off the ground. The next day the Elder confirmed that it was God’s answer to his prayers for her safety. The Elder’s concern for people was profound and, because of his suffering heart, God answered his prayers.

The power of his love and prayer for people is attested to in the following incident. Late one afternoon, while the Elder was in Athens, two spiritual daughters visited him. They left the house where he was staying after nightfall and he bade them good night with his blessing, He was anxious, however, for their safety, and as they left he began to pray earnestly for their safe trip home. He was especially concerned as one of the ladies had a problem with her knees and often fell. As they returned home, the infirm lady felt as though she was being lifted up in the air, and her companion verified that she was walking nearly a foot and a half off the ground. The next day the Elder confirmed that it was God’s answer to his prayers for her safety. The Elder’s concern for people was profound and, because of his suffering heart, God answered his prayers.

On Pascha, 1968, Elder Amphilochios received the divine forewarning of his coming repose. He was given nearly two years to prepare himself and his spiritual children for his departure. He was, nevertheless, in great agony at the thought of leaving them. In tears, he asked God that He allow him more time so as to encourage and develop his spiritual children. Shortly before he reposed he told one of them that the Theotokos, along with St. John the Theologian, had visited him and informed him that the Lord had denied his request to remain on earth through Pascha, 1970. Soon, a bout of the flu left him very weak and his condition did not improve much. Having said his good-byes and having made final separations for his spiritual children, he gave up his soul to his Saviour on April 16, 1970.

In his essay, “The Spiritual Guide in Orthodox Christianity” Bishop Kallistos (Ware) refers to Elder Amphilochios as a contemporary example of the traditional Orthodox elder:

What most distinguished his character was his gentleness, his humour, the warmth of his affection, and his sense of tranquil yet triumphant joy. His smile was full of love, but devoid of all sentimentality. Life in Christ, as he understood it, is not a heavy yoke, a burden to be carried with sullen resignation, but a personal relationship to be pursued with eagerness of heart. He was firmly opposed to all spiritual violence and cruelty. It was typical that, as he lay dying and took leave of the nuns under his care, he should urge the abbess not to be too severe on them: “They have left everything to come here, they must not be unhappy.” Two things in particular I recall about him. The first was his love of nature and, more especially of trees…A second thing that stands out in my memory is the counsel which he gave me when, as newly-ordained priest, the time had come for me to return from Patmos to Oxford, where I was to begin teaching in the university. He himself had never visited the West, but he had a shrewd perception of the situation of Orthodoxy in the Diaspora. “Do not be afraid,” he insisted. Do not be afraid because of your Orthodoxy, he told me; do not be afraid because, as an Orthodox in the West, you will be often isolated and always in a small minority. Do not make compromises but do not attack other Christians; do not be either defensive or aggressive, simply be yourself.

From the book: Precious Vessels of the Holy Spirit